Centrist imaginations

A response to a bad article, a bad book, and a bad publication

Donate to mutual aid in Minneapolis. Donate to rent funds for affected families and workers.

In a piece about the Free Press, the hardest part to write might be the introduction. This is because the form demands that I describe them, and types of people who read and work for the Free Press — including its founder Bari Weiss — often take an active delight in obfuscating or defying any reasonable description of their beliefs or affiliations. Weiss has described herself as a “liberal”, a “centrist,” and a “conservative,” among other things, and frequently prides herself on reporting that she is too right-wing for the left and too left-wing for the right (although the elite right-wing generally seems to love her, and some have openly lauded her ability to use her left-ish credentials to draw in new recruits). Her wife, Nellie Bowles, calls her a “dissident liberal.” The Free Press’ website defines itself as firmly advocating for “freedom”, “the rule of law”, and “America.” The publication rose to new heights after October 7, when Weiss — an outspoken Zionist who got her political start organizing against pro-Palestine professors at Columbia — painted the Press as a safe harbor against the mainstream media’s antisemitic lies. But, paradoxically, the ideology of the Free Press is often anchored to the premise that they have essentially no ideology at all; that they are just reporting “the facts” to “the people” as they come, speaking only as an impartial mouthpiece for those left behind by the mainstream. The Free Press, after all, was originally named Common Sense.

I’ve always been interested in The Free Press, as much as I’m interested in anything with power. Many culture-forward conservative publications (like the over-discussed Evie Magazine) feel basically like shell corporations, funded by deep-pocket private donors with seemingly little in the way of authentic readership, but I think people really do read the Press: over 1.5 million people subscribe, including many of the most powerful people in the world. Netanyahu himself recently reposted an indescribably disgusting Free Press “report” about how some of the dying children in Gaza actually had unrelated “other illnesses”; it is no exaggeration to say that the Free Press is an instrument of genocide. They were recently acquired by Paramount for 150 million dollars, and Weiss was taken on to run CBS News.

In my efforts to understand the Free Press’ culture war machine, I have recently been particularly interested in an article by staff writer Kat Rosenfield about the killing of Renee Good called Minneapolis Isn’t a Movie.

The thrust of the article, if I may attempt to summarize it in good faith, is that Good’s death can be attributed to a culture of political spectacle that convinces “ordinary people” to engage in political conflict as if it were a game or a movie without considering or even registering the real stakes at hand. Renee and her wife Rebecca Good, Kat writes, were exhibiting the “naïveté that is characteristic of many of the people, usually women, who have become the unofficial faces of this movement to hold law enforcement accountable.” Kat thinks the murder is tragic, certainly, but this culture of naïveté is as well, and she finds it her primary calling to speak truth to power mostly on the latter issue. “In 2026, political protest—and even political violence—might feel like a party, or a movie, but the one thing it rarely feels is serious, until it’s too late.”

As proof of this unseriousness, Kat cites the report that Renee Good’s partner screamed “why did you have real bullets?” after watching her wife get shot in the head by an officer of the law. To Kat, this is the key piece of evidence that activists are caught in a state of tragic unreality, unable to apprehend the severity of the world around them. It may seem “astonishing”, Kat writes, that anyone could think ICE agents would use anything but real bullets, but it “surely speaks to how Renee Good, an ordinary woman in early middle age and the sole surviving parent of a 6-year-old, ended up behind the wheel of a car, in the middle of the street, engaged in a confrontation, the true stakes of which she so devastatingly misapprehended.”

Is it? Does it? Well, not really. I suppose the reason why one might scream that question could be, as Kat suggests, because they inexplicably harbor an incomprehensible belief that ICE officers all carry prop guns like actors at Disneyworld, but it seems far more likely to me that Rebecca Good was trying to ask why they weren’t using rubber bullets or other alternative ammunition, as has been a standard practice for years against protestors in Minneapolis and elsewhere. The history of ICE and other law enforcement bodies using rubber bullets is well-documented and widely publicized; rubber bullets, while still inhumane and sometimes even deadly, are categorized as “less-lethal” weaponry and often deployed for crowd control or to “deter would-be assailants who pose a threat.” Essentially anyone with any knowledge of the situation has heard of them.

This is not the only oversight or obfuscation in the piece. Kat balks at the term “de-arresting” (meaning the strategic interruption of an attempt to arrest or detain someone) being distributed on pamphlets, citing it as another piece of proof that protestors must think they’re playing a big game of pretend — “it’s hard to overstate how fundamentally unserious it all feels,” she sniffs. But de-arresting is not a fantasy made up for Instagram infographics; it’s a controversial but legitimate protest technique with a long history of debate and refinement within organizing communities, generally considered to be most worth attempting in cases when arrest would mean deportation, family separation, or an increased risk of violence. It can work, and is often a resort of people whose lives have very serious stakes indeed. (The first result when you google “de-arresting” is a well-researched legal primer detailing the strategy’s risks; unfortunately, Kat’s only linked information on the topic is a New York Post article paraphrasing a National Review article about an Instagram post that no longer exists.)

One could be excused for assuming that the thing Kat actually finds ridiculous is the very idea of protest at all. Writing about a filmed confrontation between a civilian observer and a series of armed officers, Kat explains that the officer “understands herself to be in a dangerous, high-stakes situation” while the activist, whose child is offscreen in her car, clearly “thinks it’s all a sort of game.” How would one determine what the woman in the video believes, I wonder? What are the circumstances that brought her to this confrontation? Could the activist’s commitment to filming the agents’ activities, at great personal risk and despite direct confrontation with men holding guns, not potentially imply that she believes the stakes of this situation to be very high? We can never know for sure, unfortunately, because the linked video was posted by a right-wing engagement-bait account with no context and the woman in it is identified only as a “KAREN”; we should count ourselves lucky, then, that Kat has explained it for us.

This crack reportage has driven her to conclude that “activism and political conflict have become Disneyfied.” She shakes her head knowingly: “What was once an organized, strategic movement with high stakes and concrete political aims has evolved today into a sort of intramural sport for all comers, from influencers to wine moms to aging boomers who prefer protest marches to pickleball.” But when she gestures to this “organized, strategic movement” of the past, there’s no indication of what she’s actually referring to. Is she talking about the history of anti-ICE activism, or the history of left-wing activism in general? Is she talking about, like, the civil rights movement? (If so, does she think celebrities, mothers and elderly people did not engage in the 1963 March on Washington?) The sloppy writing here serves, purposefully or not, to slip in an important political point: it helps create the feeling, as many Free Press articles aim to do, that the inherently empathetic and reasonable author believes progressivism is not all bad — it has some unspecified good ideas, some heart, even at a point some real potential — but that the excesses and entitlements of the modern era have sadly wrenched it astray. (It’s conveniently up to the reader to determine where or how exactly the movement went too far.)

But for all her preening about how leftists don’t know the score, it is Kat who engages in a self-indulgent fantasy. The craven fanfiction she writes about Renee Good, presuming not only to know what she was thinking and feeling before the moment of her murder but also assuming she had been tricked into conceiving of political conflict as a “play-acted” sort of “‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ ride” that she engaged in because she wanted to “join the party,” is not just cruel, disgusting, and disrespectful: it is the kind of plain stupidity made possible only by a profound belief in one’s own intelligence.

The Free Press’ house style slouches towards Didion, clearly aiming to imitate the New Journalist’s signature mode of sharp, humane, observational criticism. Joan Didion’s conservatism, though, was anchored not only by an unreplicated prose style but by a consistent conviction to let her subjects speak for themselves. Her most cutting pieces on the idiosyncrasies and excesses of leftism — her delicious piece on Joan Baez’s school for nonviolence, for instance, or her profile of a proud Marxist-Leninist — take place on her subjects’ own turf, in their own words. The most scathing moments those pieces, in fact, derive mostly from direct quotes presented without much extrapolation. Didion’s curiosity about her subjects, and the journalistic and social ability necessary to get them to open up to her in the first place, is what elevated her from being just another striver writing for the National Review into a monocultural titan of letters — with a body of work that has remained widely appreciated for decades by feminists and communists alike (me included) despite its frequent criticisms of both. Even when I don’t entirely agree with Didion’s send-ups of progressive culture, her direct engagement with the communities she wrote about has almost always allowed me to see myself more clearly.

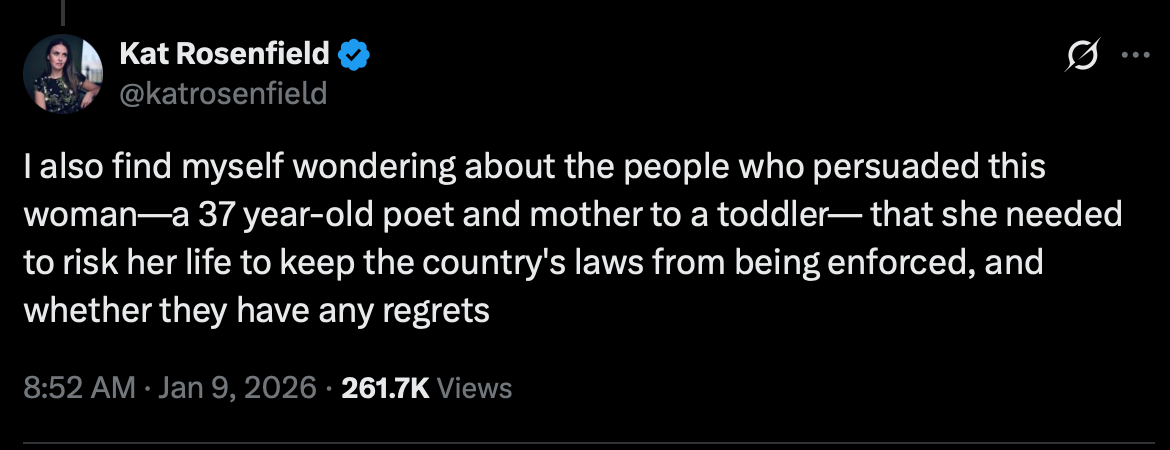

Kat clearly aims to produce the same kind of aisle-crossing wisdom. But if she’s gleaned insight from anything other than her own viewing of viral videos online, there’s no proof of it on the page. Most of her argument is anchored on amateur analysis of blurry videos posted by the official Homeland Security X account. I cannot be driven to meaningful self-reflection by her work, because her guesses about the psychology of the left are based in nothing and resonate with no one beyond the similarly overconfident and under-informed. On X, she’s defended her piece by suggesting that it was simply an attempt to “understand” an event she finds “heartbreaking.” It’s an interesting choice, although maybe not an intelligent one, to search for understanding not through outward inquiry or research but solely within your private repository of what you already believe.

Molly Fischer makes a similar critique in her New Yorker review of Morning After The Revolution, a book about the follies of progressivism by Free Press cofounder Nellie Bowles. The book aims to report on the craziest foibles and most damning contradictions of the early-2020s “woke era,” framed through Bowles’ own journey from tote-carrying “progressive” to ideological black hole. Bari Weiss, who is Bowles’ wife, has described her as Joan Didion meets Tom Wolfe. But as Fischer writes, Bowles’ interrogations of the left rarely have the intimacy or access necessary to justify the comparison, or even to engender writing that’s baseline compelling at all:

“...Bowles seems hesitant to engage personally or at length with the revolution’s foot soldiers. The people she speaks with instead tend to be the irritated neighbors, bewildered bystanders, disillusioned allies, proponents of moderate alternatives, and officials with talking points. The voice of the revolution comes from public statements, whether quoted in the media, posted on the Internet, or shouted at protests. The primary voices in a chapter on trans children… are doctors and medical administrators whose quotes seem to come from lectures and videos available online.

Some figures whom Bowles considers… decline to be interviewed. At demonstrations, protesters regard her warily and sometimes block her view of their activity with umbrellas… Her account of a trans-rights protest leans on quoting things yelled by a person Bowles calls “Green Shorts,” who was wearing green shorts and yelling. Didion described herself as “bad at interviewing people”; still, she managed to sustain a level of intimacy with her subjects sufficient to get behind closed doors and see, say, a child on LSD (as in one famous scene in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”). “Writers are always selling somebody out,” Didion warned, but Bowles never gets close enough to expose anything sensitive to public view. You can’t sell out a stranger on the street.”

It makes sense to me that leftists won’t talk to Nellie, due to the fact that her publication is awful and her stilted, self-satisfied sense of humor makes her sound like an undercover police officer. (The Free Press sent me an interview request when I was 21, and I remember laughing out loud on the subway car when I got the email.) But it’s a tough sell, in both her case and Kat’s, to try to conjure an air of worldly wisdom when the world has not opened itself to you. The result reads like the gonzo journalism of someone who isn’t cool enough to get in the club, like if Hunter S. Thompson had been turned away from the Kentucky Derby for having a weird vibe.

Still, Bowles is right that leftists can be crazy, corporations can be insincere, and grifters in politics, business, and the non-profit sphere alike commandeered the horror of racial violence for personal gain (if this was news to anyone in 2024, I can’t imagine who; why her old editor reportedly began to find her anti-woke story ideas uninteresting, I also can’t imagine). Her targets, though, are muddled: the “Brooklyn left”, armed antifa supersoldiers, corporate Twitter accounts, and major political leaders are often rhetorically lumped together under the vague umbrella of the movement or the revolution, making it difficult to parse any real materialist analysis of the moment. The nonbinary anarchists carrying AK-47s at CHAZ are surely not the same people hitting an earnest “like” on Oreo’s statement of trans solidarity — in fact, the former’s criticisms of the latter are surely numerous, and probably immortalized in a series of zines far more incisive and impassioned than any of Bowles’ writing on the subject. So, as with Kat’s work, the book’s fatal flaw is not just that it’s morally wrong or politically repugnant but that it’s sloppy, imprecise, and indulgent, with the writer’s own idea of themselves as a dissident intellectual clearly overtaking their commitment to actual intellectual or anthropological rigour.

These oversights may be explained in part by the fact that Bowles was never really particularly left-wing in any meaningful sense (her listed bona fides include attending one event by the Nation, voting for Hillary, being gay, and feeling anxious about succeeding in her workplace1). The overconfident unfamiliarity with the communities she presumes to expose results most of all in a feeling of boredom: with nearly every example of left-wing silliness I read about in her book, I kept thinking that I could name twenty crazier things I’ve heard leftists say or do off the top of my head. I can do this because I actually am one, and because I actually know them, too, and because we have struggled together into adulthood through a strange, scary, alienating, polarizing, violent period in history in which we all went crazy but tried our best to be around each other anyway. I love leftists with everything I have, and I complain about them constantly, and have hurt them and criticized them and made fun of them and failed them and had all the same done to me by many leftists in return. The people I know have been manhandled by police at protests, received visits at home from federal agents, spent nights (or longer) in jail. They’ve pushed through incomprehensible pain and grief to help the people around them at no personal gain. They’ve watched people die who should have lived. They have dedicated themselves again and again to staring the worst parts of the world in the face, and then dedicated themselves tenfold to feeling profound hope anyway. They accept harder, scarier, more punishing lives because they refuse to accept the moral compromise of an easier one. While reading Kat’s piece, I think: These people know about stakes you can’t imagine. While reading Nellie’s, I think, I wish you knew what you were missing.

I’ve seen self-professed leftists do horrible things, too, incomprehensibly awful acts of cruelty and evil. I’ve seen all kinds of people do horrible things, really. The core of my ideology is not, as Bowles claims about the new left,2 that all people are perfect angels who cannot and will not do wrong of their own accord. The core of my ideology is that the world is a functionally horrible place full of deeply compromised people that has the potential nonetheless to be redeemed by love and effort. This is not such a crazy idea. It’s basically in the Bible.

Writing this piece is a losing game. In order to criticize the Free Press’ failures, I have to do something they refuse to do with so many of the subjects they write about: I have to be interested in them. I have to engage with their right-wing sources, their cherry-picked clips, their insistence on using people’s most vulnerable moments as evidence of the broad psychological thrust of the public as a whole. The words that Renee Good’s wife screamed at the ICE officer shouldn’t even have to make sense, because the person that said them is a civilian who just saw their partner get shot in the head in front of her. By engaging in relatively civil debate with these people — really, by doing anything with my week other than actively impeding ICE operations with my physical body — they have turned me into a kind of moderate, too. The centrist pulls you down to the level of discourse and beats you by wasting your time.

The fact that Kat’s research is so poor and her logic so vacant only serves to underscore that the ultimate goal may not be to actually convince anyone of anything so much as it is to pursue the cyclical proliferation of discourse itself. Rather than valuing conversation for its ability to generate politics, the Free Press liberal believes that the end goal of all politics is to generate conversation. To engage in argument at all about the assumed technical meaning of words screamed in anguish by a woman covered in her wife’s blood is, no matter what, to validate the Free Press’ most insidious and fundamental tenet: that everything can be and should be up for debate.

But I’m interested in the ways these pieces fail. I think the specific nature of their failures indicates something interesting about the types of people who wrote them, which are also the types of people currently set up to change the face of mass media as we know it. A Fox News piece, for instance, would typically not fail in the precise way these pieces have failed because Fox generally does not presume to earnestly understand or empathize with the left. But the Free Press’ politics of decorum — their enduring desperation to be a pleasure to have in class — demand the performance of even-handedness, the veneer of empathy, the declaration of a soul; they are writing, after all, for people who retain the fundamentally liberal obsession with being perceived by others as good. The “dissident liberal” is so annoying precisely because they combine the conservative’s politics with the liberal’s steadfast belief in the supreme moral value of personal feeling. “I say explicitly, in the essay, that I find it heartbreaking, haunting, and tragic,” Kat said mournfully on X in response to her article being lightly criticized in New York Magazine. “How you could miss this, I can’t imagine.” My first thought was that she was pretending to be stupid on purpose in order to waste everyone’s time, but to her credit, she seems genuinely confused; it doesn’t seem to compute that nobody cares how many times she put the word “tragically” in her essay about how activists are deluded children, nor that considering murder evil is more important than considering it sad.

Here, the Free Press’ dissident liberalism joins hands with the institutional liberalism it supposedly left behind: both ideologies tend to feign a middle ground by acknowledging the feelings of the left while accepting the policies of the right. While the conservative might say bleeding heart leftism is the purview of brainwashed blue-haired wokies, the Free Press centrists often prefer to insist that their hearts bleed, too, while they march in the same line as the fascists. “[Drug dealers] probably are victims too, in a million ways,” Bowles proclaims earnestly in a talk celebrating the release of her book. “They are probably supporting a family in Honduras. But, also, you have to arrest drug dealers.”

As reward, adherents of this ideology gain access to a double superiority complex: in company with classical conservatives, they get to feel like paragons of empathy and compassion; in contrast to lefties, they get to feel like the adults in the room, making the tough calls through their unique faculties of judgement and common sense. While they often complain about being “tribeless” or “politically homeless”, they in fact prefer it this way, because a political home requires more of you than just cultivating opinions — and they don’t want to be in any club that wouldn’t have them as a member.

To Kat’s credit, the scenes from Minneapolis do look like a movie. The elderly man screaming in rage before being enveloped in tear gas, the woman using her walker to march into the protest line, the throngs of civilians in gas masks holding cameras and blowing whistles, the 46-year-old driven to participate in his first act of protest after seeing ICE agents mocking the flowers from Good’s memorial — if you were particularly cynical, I could see how those moments might feel like imitations of some imagined film, acted out live by protestors subsumed by the spectacle. An alternative interpretation to consider, though, is that it might look like a movie because movies so often attempt to reflect the human bravery and human evil that have always been authentically present in real life.

One of the axioms upon which Kat’s article is built is the idea that there exists a class of “ordinary people” who belong categorically to a world outside of political conflict. Renee Good was an “ordinary” person, and so her presence at a site of political activity must necessarily be an aberration, a miscalculation, the result of foul play. Despite running a magazine that prides itself on being by-and-for elites,3 Bowles and many of her ilk share this ideological quirk — referring again and again to an imagined silent majority of “normal people” who fundamentally agree with them on everything that matters (its all Common Sense, remember?). Normal people don’t believe any of that crazy fringe stuff, they explain: if it ever appears otherwise, it’s either because they have been bullied, shamed, or manipulated — the assumption seeming to be that all people are born centrists, and any other political inclination is a performance, a phase, or else a kind of genetic deformity. Listen carefully and you can hear the contempt that rich centrist types hold for the “normal people” they invoke so regularly, how stupid they think they are. Normal people just want good schools, clean streets, a healthy culture of policing; they’re people with families, people with jobs, people who prefer lives of simplicity and comfort to lives of chaos and revolution. They could surely only be driven to engage in street politics if they had been tricked by a duplicitous culture into thinking there were no stakes, no risk; surely they just got lost on their way to a strip-mall escape room.

Almost everyone, to be fair, can participate in a kind of flattening sentimentality regarding their own idea of “normal people”. So let’s just call them people, then, the people in the videos and on the streets, the people who have jobs and kids and and the people who don’t, the people who rush to Chinatown when they hear about the surprise raids, who get out of their cars when they see men in masks harassing a stranger on the street, who march for hours in the cold, who try and often fail but try again to make the world better in the ways they know how. An estimated 50,000+ people participated in the anti-ICE march in Minneapolis last week, and while I think it would be totally swell if they were all card-carrying communists, they’re not — they’re all kinds of people, some without any professed ideology at all. I don’t think many of them had to be persuaded or propagandized into caring about the people in their communities, or into wanting ICE off their streets. It makes sense that they might be angry about being told what to do by people they don’t know (this is perhaps the most “normal” trait it is possible for an American to have). Some may have learned about “de-arresting” on Instagram; some may have learned it from an organizing meeting; some might just have an instinctive sense of who their enemy is and who it is right to protect. Most are moving with specific motivations, ideologies, and histories that I can never know or fully understand. Any attempt to group tens of thousands of people into one coherent category will necessarily fail. But none of this action seems so strange or inexplicable to me. People, in all the ways I have known them, are often brave. They see horrible things happening and work very hard to stop them. They care a lot about people they don’t know and are easily moved to help them. They are willing to put themselves in danger in the pursuit of what they believe is right.

It is easy to believe that people perform these acts of bravery because they are uninformed, or deluded, or because they think they’re in a Marvel movie and would like to be a star. It’s easy because it turns your abstention from these messy acts of politics into an act of moral and intellectual clarity. The reality may be tougher to swallow, but it is also much simpler: these people know the cost of things better than you ever will, and they have chosen to be brave anyway.

I attended an anti-ICE protest recently. It wasn’t a very “serious” protest, as protests go: it was very peaceful, very public, hardly the kind of thing you have to put your phone on airplane mode for. My friends and I rolled our eyes at the flippant signs and the handful of people taking pictures, and we cried afterwards at how little we had accomplished, how powerless we felt. It didn’t feel like the revolution. But it wasn’t a party or a game or a Disney ride, either. The people around us were mostly angry and sad, marching slowly in the freezing cold, some holding photos of dead people and missing children. That’s what got me, really: I’d see a few dumb posters and teeter on the edge of feeling superior to the whole thing, and then I’d see another photo of a dead person clutched in a pair of mittens.

And then you read these fucking losers who think they get to tell you what life is like. As if they have any idea. Sometimes your kid is in the car when you drive past an ICE abduction and you have to pull over or another person could be taken, gone. Sometimes the feds provoke you to react so they have an excuse to throw out more tear gas or to start arrests and it works because you haven’t slept in a week. Sometimes masked agents invade your community and you have no choice but to join the cause inexperienced, confused, scared, as you are, because they’re literally outside your front door. Sometimes you watch someone die on your phone and you can’t do anything for two days but shake and cry. You go to the protests. You send the money. You join the Signal group. It’s not perfect, this stuff, but it’s real. Everyone knows it. You can feel it vibrating in the air, the feeling that no one knows what to do with their pain and fear and anger, their ache to live in a different sort of world than this one — everyone is pawing desperately in the dark for some better way forward, some way to help each other through. We struggle through this failure of catharsis together. We try to figure out what we’ll do next. That’s real life; that’s politics. Maybe it feels like a movie to the writers at the Free Press because they’re the ones watching it all through a screen.

Donate to mutual aid in Minneapolis. Donate to rent funds for affected families and workers.

Thanks so much to Liam, Anne, Jake, and Maris for your thoughtful feedback on this piece.

Radical lefty rag the New York Times!

“[The ‘New Progressive’] came with politics built on the idea that people are profoundly good, denatured only by capitalism, by colonialism and whiteness and heteronormativity... The police could be abolished because people are kind and—once rescued from poverty and racism—wouldn’t hurt each other… The New Progressive knows that people are good and stable, reasonable and giving.”

From NYMag: “The Free Press also generated a positive-feedback loop among Weiss’s network of wealthy supporters, magnifying her reach and influence. “The unifying ideology of the Free Press is that it’s all things a rich person would agree with,” said a New York–based media operator. Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos, who met Weiss at a dinner party held by former agent and super-connector Michael Kives, told her he liked her podcast series The Witch Trials of J. K. Rowling. At an event at Grazer’s house, Katy Perry told Weiss she was a reader. “Her intended appeal was to not just be a mouthpiece for the elites of the East and West Coast but, at the end of the day, the Masters of the Universe — that’s whose support actually spreads things,” said a former adviser to the company.”

I agree fully that the iteration of discourse seems to be the point of articles like the one Kat wrote. I made a series of attempts toward good-faith debate with Kat in the comments of her piece, but she refused to admit any kind of premise that would explain the dismissive language she uses to describe Pretti and Good’s killings. Instead the best she could do was bizarrely claim that her post “isn’t about politics,” that she’s somehow “not writing about ICE, or the protesters, or the clash between the two.” Instead, she claimed to be writing about the vagaries of the “contemporary media landscape,” which (and this is exactly her strategy) is broad to the point of meaninglessness. She’s not interested in discussion because, like you said, she’s figured out she can churn out arch drivel to launder right-wing arguments with faux-liberal sensibility.

You're right about all this. There are so many lines here I want to remember forever:

"I have to do something they refuse to do with so many of the subjects they write about: I have to be interested in them."

"It is easy to believe that people perform these acts of bravery because they are uninformed, or deluded, or because they think they’re in a Marvel movie and would like to be a star. It’s easy because it turns your abstention from these messy acts of politics into an act of moral and intellectual clarity"

"to feign a middle ground by acknowledging the feelings of the left while accepting the policies of the right."

The rhetoric that there's "someone" who pits normal good people against each other only sounds good to people who see these things as having no real stakes.

This is great thinking and writing.

I am als, interested in the Free Press and I don't want to be, for a different reason: Good's story is not one of them, but there are some "Ok, people on our team did a bad thing/was wrong" stories that are being funnelled there because respectable sources aren't ready to print them.