Somewhere between hyper-capitalist motivation videos, pseudo-spiritual tweets, and Instagram therapy infographics, a predominant mental-health narrative has emerged on the internet. It takes many forms, but is perhaps best defined by its penchant for isolation: it begs you to “focus on yourself,” to “protect your peace,” to sever relationships that don’t serve you and invest your newfound time and energy into self-improvement. Seductively, it whispers that you “don’t owe anyone anything.” It glamourizes — and moralizes — a life spent alone.

Sometimes, it’s dressed up in the aesthetics of corporate self-optimization: on Instagram and TikTok, viral inspirational videos collage high-contrast images of fit, light-skinned men and women studying (alone), working out (alone), going to therapy (alone), or sometimes positioned (alone, despite all contextual logic) in a party dress or tux on a New York City rooftop. As lives go, this one has a beautiful sales pitch; the videos paint a world without conflict, without pain, without uncertainty, without the tidal waves of emotion that often leave me bedridden or sobbing on the streetcar. Yes, these people may be setting up their shots by themselves, but they’re also beautiful and rich and seemingly content. The best thing about tripods, I’ve heard, is that they can’t hurt your feelings.

Alongside all the lifestyle porn is a slew of public-facing therapists and mental health influencers who promise to help you become the person you’ve always wanted to be. In her essay Less TikTok, More Screaming, Persinette writes that these e-therapists have turned healing into “a religion, a lifestyle, and above all, a brand” while promoting a culture of isolation and individual optimization. In this ecosystem, “...therapy has become a litmus test for social belonging and inherent goodness, a sign that one is aware of and has adapted to the newest standards of how to behave.”

The social standard this culture offers is one of controlled, placated solitude. Its narrative often insists that you’re surrounded by toxic people who are trying to hurt you, and the only way to ever become the person you’re meant to be is to cut them all off, retreat into a high-gloss cocoon of talk therapy and Notion templates, and emerge a non-emotive butterfly who will surely attract the relationships you’ve always deserved — relationships with other “healed” people, who don’t hurt you or depend on you or force you to feel difficult, taxing emotions. And finally, your life will be as frictionless and shiny as you, alone, have always deserved for it to be. (A frictionless life is your reward for hard work, by the way, and people who don’t work hard don’t deserve good things. DO NOT google Protestantism.)

I’m sure that the world of anti-social wellness culture is familiar to many of the readers of this essay; we’ve all seen the viral text-message templates and disturbing Reddit posts that typify the movement. For some of you, I’m sure this culture has also been relatively easy to reject. I, for one, have always found it almost too easy to look down on this movement, with its “Go To Therapy” t-shirts and its buzzword-laden infographics; it’s only recently that I realized I’ve spent my life indulging an eerily similar and far more insidious flavour of isolation.

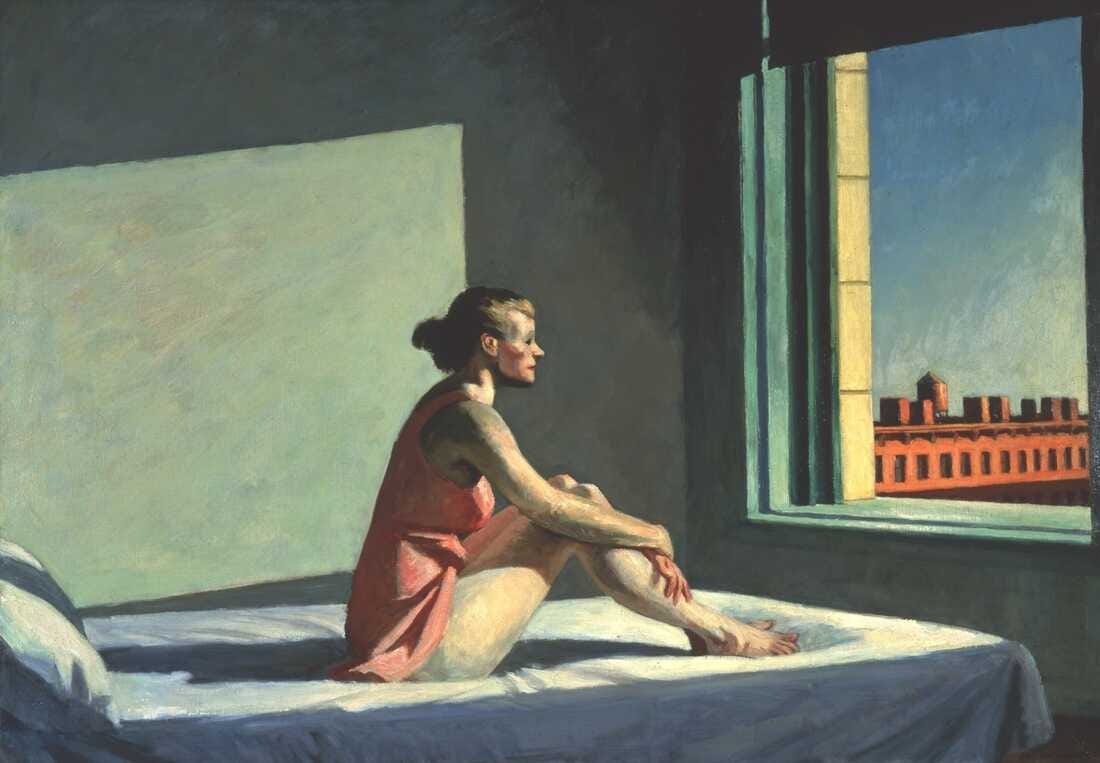

Here’s the long and the short of it: I may have never felt the need to cut my friends out of my life in service of my own optimization, but I still don’t answer their texts. I can’t help but feel crushed by the weight of what I owe to my community, certain I’m going to hurt the people I’ve fooled into loving me, convinced that I’m doing them a favour by icing them out until I get myself together. I am too loud, too self-involved, too insensitive, never caring enough or attentive enough or possessing enough natural kindness. I have made people I love feel alone when they needed me; I have been cruel to people I never wanted to hurt. Like many — dare I say, most — people in their early 20s, I find it hard to shake the feeling that my life is a pinball machine of relationships and opportunities that I’m hurtling through headfirst, knocking over bystanders and crashing into obstacles, unable to stop for long enough to figure out what I’m doing wrong. It is tempting, in this world of alarm-bells and flashing warning signs, to want to trap myself in a room where there’s nothing to bounce off of but myself.

The worst thing about this feeling is that it makes you a martyr. You may hate yourself, but you’re also a hero, bravely forgoing love and connection and community to protect the world from the car-bomb of your own instability. You sit in your room and tell yourself lies: that they don’t want to hear from you anyway; that you’ll wait here alone writing Notes app soliloquies until you become good enough to deserve other people; that it is a noble endeavour to punish yourself.

And so I ignore my friends’ texts. My motivations tend to skew self-destructive rather than ruthlessly self-optimizing, but I’m beginning to suspect that there’s hardly any difference worth writing about. Doesn’t aspiring to construct a perfect self imply a desire to destroy the current one, anyway?

Martyrdom feels entirely at odds with the self-optimizing solitude you see advertised by Instagram infographics and Twitter therapists — if you relate to one of the two phenomena, you likely feel completely repulsed by the other — but I think they are far more like mirror images than opposites. Both strategies rely on the fantasy that isolation can eliminate harm to yourself or others. They both use the idea of your own healing as a metric for the kind of relationships you deserve to experience. Both centre around the same fundamental belief that we have to be perfect in order for people to love us, or to be deserving of the love we’ve been given. Most damning of all, they are both infected by the same rotten premise: that it is possible, even ideal, to get better by yourself.

It’s an intoxicating idea in part because isolated healing is a study in false negatives. When relationships are made difficult by traumas, anxieties, and neuroses — and when those issues are triggered as you navigate complicated relationships — being alone really can feel a lot like being cured. Relationships with other complex, flawed people are beautiful and transformative and fulfilling, but they’re also inherently maddening, infuriating, hurtful, stressful, and yes, triggering. It is ideal, of course, for us to work to understand those conflicts and thereby make them less destructive to ourselves and others, but we can’t make those feelings disappear; nothing real can have contact without friction. If you’ve been encouraged to define a healthy life as a frictionless one, I think it may be inevitable that a life devoid of contact starts to feel like healing.

And here’s the thing about friction: it really does hurt. Isolationists have one very strong argument on their side — when you’re alone, there’s no one there to hurt you, even accidentally. There’s no one there to throw your own flaws into stark relief. There’s no one who you might hurt with bursts of uncontrollable emotion or human carelessness. It’s hard to be hurt, and perhaps even harder to hurt the people you love — why not cut the risk, lock the doors, and live a life of robotic, impersonal, action-oriented optimization?

The answer, of course, is that none of us are any good alone.

It is a cruel and fundamentally inhuman tragedy that the culture has convinced so many of us that we must be healed in isolation, because being surrounded by people — people who love us, or care for us, or are willing to sit in the same room with us while we clean up our messes — is about the only way that I, for one, have ever been able to get better. I am lucky enough to have been changed again and again and again by the people who have loved me or challenged me; I look back at the person I was at eighteen and I hardly recognize her, which feels like a miracle and a tragedy all at once. Standing between me and my younger self are a thousand different individual experiences of failure and growth and redemption, each a moment of excruciating vulnerability being witnessed by the very people I wish could only see me at my best. It’s driven me to isolate myself, convinced that ritualistic self-punishment and pathetic martyrdom were the only ways I could ever make myself worthy of other people. I realized, though, that I was being a coward. Being alone is hard, to be sure, but it’s also deceptively easy — it requires nothing of us.

People, on the other hand, challenge us. They infuse our life with stakes. You can hurt a friend or partner or lose them forever if you refuse vulnerability or reject growth — the same cannot be said of a therapist, for instance, which makes them far safer companions. Therapy, while genuinely beneficial in many forms, has started to become homogenized in the personal-wellness zeitgeist as a kind of resume-builder for the self; a box to check off on the way towards becoming a hyper-functional young professional in life and love. “I only date people who go to therapy” has become a nearly unavoidable refrain in dating app bios and viral tweets. Many of us conspicuously signal our enrollment in therapy in order to make ourselves more viable candidates for love and friendship — to show, again, that we are doing the work that will make us worthy of salvation. If you go once a week, pay $200 a session, scribble in the worksheets, have the tough conversations, and Do The Work, perhaps you can come out the other side clean and clear, unblemished by uncontrollable emotion or idiosyncrasy or errant needs. It’s a satisfying transaction, to be sure — one that gives people the quantifiable markers for success that form the fundamental currency of capitalist society.

I’m not trying to discount the genuine benefits that therapy can provide. A good therapist really can help you notice your blind spots, recognize and process your emotions, and build healthier relationships, and I know many people (including myself) who have reaped great benefits from therapy. My problem is the positioning of a one-size-fits-all solution as the only way to become a good, functional, whole person — and the idea that one must be “whole” in order to love or be loved.

It almost goes without saying that having mainstream therapy be a social prerequisite for community and connection is a deeply exclusionary practice: most therapy is prohibitively expensive, and the psychiatric institution can be a deeply traumatizing and destructive force in the lives of many mentally ill people. But even outside of the material barriers imposed by this kind of standard, I am troubled by its implication: it insists that healing is a mountain to be climbed alone, and that relationships are the reward we get once we’ve reached the summit. When we insist that we could only ever effectively love someone who’s been perfectly “healed” — who will not struggle, accidentally hurt us, trigger us, say the wrong thing, do the wrong thing, or participate in any other uncomfortable display of humanity — we are reinforcing, and perhaps projecting, our own beliefs that we have to be perfect in order to be loved.

There is one way to reject this: make the choice to love someone who is as flawed as you are. One of the most remarkable pleasures that love has to offer, in fact, is the feeling of meeting someone who is scarred and beat-up and bruised, too emotional or not emotional enough or oscillating wildly between the two, and offering to love them enough to help them get better (and, of course, to have them do the same to you). To grow beside a friend or lover, knowing that you will poke and prod at each other as you take shape but unafraid of the resulting scar tissue — this is the good stuff.

Call me conspiratorial, but when I see the brightly-coloured Instagram posts encouraging me to cut off my friends and focus on myself, I can’t help but notice a convenient side effect of isolation: it forces us to rely on paid relationships in order to grow. The relationship between you and your therapist is transactional and safe, free of the messiness of attachment or stakes or love. And there are times, to be sure, when that can be a very useful relationship to have. But a serious issue arises when professional, unattached relationships are positioned as a replacement (or a requirement) for fulfilling, challenging, passionate ones. When people say that one ought to go to therapy to become a perfectly stable, functional, “healed” individual before they dare try to experience love or community, they are imagining a world in which a fundamental purpose of human connection has been replaced with a capital exchange. Welcome to the ideal relationship: one between two perfectly realized individuals who would be totally fine alone but choose to hang out because they like splitting rent and watching Law and Order. No passion, no growth, no difficult conversations — that’s your therapist’s job.

To be clear, the idea that it’s not our job to “fix” one another is a piece of pop conventional wisdom that developed, at least in part, for understandable reasons. It’s undeniable that people (usually women) can be expected to manage a vastly unfair share of emotional labour in their relationships, often at great personal expense. We are encouraged to ignore abusive behaviour for the sake of our abusers or told that abuse can be prevented by becoming more generous, more loving, more permissive. This is both deeply damaging and patently false. It’s never your responsibility to make someone stop hurting you, whether they mean to or not — and I don’t think you can truly help someone while they’re hurting you, anyway. If we agree that our well-being is inexorably linked to the well-being of our communities, it becomes clear that nothing generative — nothing truly healing — can come from destroying yourself trying to save someone else.1

Believing in the power of love and community as a redemptive force doesn’t mean that we should give ourselves endlessly to everyone around us. I’ve had to remove people from my life because their circumstances made it hard for them to stop hurting me in some way or another, and I’ve had people remove me from their lives for the same reason. These were sad and difficult times in which we all learned that it is often impossible for us as individuals to save someone we love from the sum of their suffering, especially so when you’re ignoring your own needs in the process. But to extrapolate that reality into the idea that we shouldn’t want to tend to our loved ones, to receive them as flawed and imperfect people and care for them anyway, is a grave miscorrection. We all exist to save each other. There is barely anything else worth living for.

Rather than being a gradual, non-linear journey towards realization and fulfillment, we’ve begun to imagine "healing" as a series of personal-discovery tasks that exist to make the self more comprehensible. We’re encouraged to enumerate our flaws, systemically comb through our childhoods for neat, pert little stories that can explain how each of them came to be, and then destroy them. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to understand ourselves.2 But if going to therapy has taught me anything, it’s that nothing is actually solved by intellectualizing and pathologizing every part of what we feel — and when we try, we’re usually sort of wrong anyway. Your emotions, by and large, are not a problem to be fixed in service of producing a better, more manageable, more loveable self. They just want to be felt.

The process of becoming yourself is not a corporate desk job, and it is not homework, and it is not an unticked box languishing on a to-do list. You do not have to treat your flaws like action items that must be systematically targeted and eliminated in order to receive a return on investment. You have no supervisor; you should not be punished when you fail. Your job is not to lock the doors and chisel at yourself like a marble statue in the darkness until you feel quantifiably worthy of the world outside. Your job, really, is to find people who love you for reasons you hardly understand, and to love them back, and to try as hard as you can to make it all easier for each other.

It’s hard, certainly — it’s painful and exhausting and fundamentally terrifying to rip yourself open and leave the guts at the mercy of the people you choose to love. But if I know anything, I know this: It’s better than being alone.

thank you for reading this essay!! internet princess is a reader-supported publication. if you’d like to help make my writing possible, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. <3

my wonderful friend CJ The X helped me talk this part out. they are very smart both in conversation and on their youtube, which you don’t even have to be friends with them to watch

loved this! made me think about the discourse around the rupaul-ism "if you cant love yourself how the hell are you gonna love somebody else" and its like well...... loving other people and allowing myself to be loved by other people has been instrumental in learning to love myself.

This is an incredible essay. It got me thinking about how mental health really is commodified to an almost comical degree. Yes, therapy or medication can improve many people’s lives, but when antidepressants are bottled with minimalist design and a trendy font, or an app promises a happier life for just $12.99 a month, or self-love seems dependent on certain products, like a wellness journal or affirmation cards, it all becomes so dystopian. Thank you for the reminder—loving ourselves and each other can be ugly! And wild! But that’s what it’s all about. It’s in our nature to rely on one another.